There’s a wildly popular franchise that started in our neighborhood that converts warehouses into dazzling bright white indoor playgrounds. Think: a McDonald’s PlayPen, but—are you ready to be dazzled?—in bright white. Like an Apple Store.

Many of our parent friends enjoy this place (and some of them I might add are very good people). It’s based on one of those highly Instagrammable immersive ‘art’ experiences like the Museum of Ice Cream. There’s a jungle gym made of ladders and precarious nets held together by PVC pipe and zip-ties, a ball pit the size of an olympic swimming pool, and textured walls. There are tubs full of choking hazards I mean beads, and a room I like to call the strangulation chamber, with plastic ropes of different lengths hanging from the ceiling. All bathed in the kind of lighting that makes one feel high on drugs or inside of a David Lynch film. While interesting in those situations, believe it or not this type of lighting can be quite panic-inducing in others, like, for example, when searching for a small child.

I try not to be a hater, you know I try, but it’s all a bit Willy Wonka for my taste.

A membership costs $300/month and grants access to exciting extras like tubs of a patented playdoh-like substance made of god knows what. Single entry for $50 doesn’t include that, but you try explaining to a toddler he can’t touch slime with the other toddlers because he isn’t a member.

The company also provides signature color block socks ‘free’ at every expensive entry, making kids’ bodies into walking advertisements wherever they go, which is simply brilliant marketing, and not sinister or exploitative at all.

I suppose if my child hadn’t broken his leg on an oversized bouncy castle there, I might still be tagging along with my mom friends when the weather was bad—complaining the whole time, but they’re used to that with me. But as it is, every time I come across one of those infernal socks at the bottom of my drawer, I march it straight to the trash.

For some reason, as we sped to the hospital that day, N screaming in pain in the back seat, I became carsick and started throwing up uncontrollably out of the window onto the BQE. Since that day, I’ve thought a lot about this space.

Now I’m not saying a child’s life has to be all washing the table and polishing the cup like Maria Montessori intended. Surely there’s a time and a place for chocolate rivers and candy wall paper—the odd Willy Wonka experience.

But I do seem to remember a certain complex morality at the heart of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. I’d go so far as to say any time a ticket promises families the wildest fantasies of children come to life, you can bet on a PT Barnum or Oz-like hum-bug pulling strings behind the curtain.

McDonald's introduced its play pens during the height of the ‘stranger danger’ panic. As constant news coverage of child abductions made parents fearful of public space, McDonald’s sold families on its enclosed, private playgrounds. The sense of safety was, of course, 100% illusory, and, due to horrifying sanitary and safety concerns, McDonald’s has since almost completely phased them out. (-Mental Floss).

Replacing the conditions of the real world with high-design alternatives simply introduces alternative risks.

In all my reading and experiences with childcare, I find myself very drawn to this idea of the real, and the ever-present option as adults to present children with constructed alternatives.

For me, it’s always been the most indelible insight of Montessori philosophy: her views on the child’s relationship to reality and ‘practical life.’ Montessori believed that tangible interactions with the real world were essential for a child’s development, which is why she insisted they use real glass, real knives, and take part in self-care and cleaning tasks as soon as they could walk.

And one of the hardest aspects of Montessori’s philosophy for me is her belief that young children should not be exposed to fantasy until age six(!) when their grasp of reality is more developed.

“Reality is the true basis of imagination,” she wrote. And even though my child is obsessed with fantasy, I think about this often.

I wonder why this idea has so much pull for me. What would it mean for a society to honor and protect a child’s relationship to reality. There would be no need to create fantastical concepts for them out of plastic or warehouse families for whom the stresses of childcare necessitate total breaks with the real. She is saying there is no alternate space that is somehow better suited, more fun, more heightened, or more engaging for children than reality itself.

And if we accepted that children belonged in the real world, we would also accept that the real world should be an accommodating place. It would mean endorsing true inclusivity, even for the least capable and least independent among us.

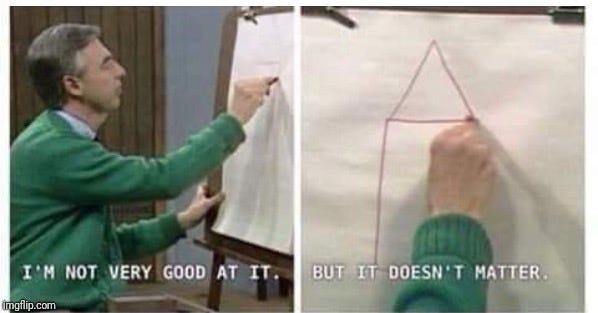

It’s the same reason I love when Mr. Rogers takes kids into factories and bakeries and the homes and schools of real kids. I’m especially amused when he emphasizes his ignorance about the way things work. He’s not exaggerating, exactly, he’s demonstrating. He’s inserting his child-like modality (that we all inhabit at times), and in the real spaces he enters, it’s fully welcomed. These moments in the show quite frankly stun me with their kindness. He’s modeling what a mutually respectful relationship between kids and the real world could look like.

In Japan, I was thrilled to find out that kids study cooking and cleaning in school in full academic units where they have to bring in vacuums from home and learn to use them. And of course, small children famously run complicated errands for their families, making train transfers and lugging heavy bags of groceries. Obviously this is adorable. But it’s more than that. It speaks to the standards Japan has for its society, the agreement that everyone will contribute as they can, and that public life will be safe and navigable for all.

One of my favorite parenting books I’ve read is Hunt Gather Parent by Micheline Ducleff. In it she talks about the “W.E.I.R.D.” child-rearing ways of “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic” nations. One of the weirdest things we do is create special activities for kids, sequestered from the rest of the social world. In the author’s view, it leads to high-conflict relationships between parents and their children that would seem foreign and bizarre in many societies.

She makes an important distinction between independence and autonomy in the book. WEIRD societies value independence, but not autonomy. Independence is the ability to run wild, do a backflip into an olympic swimming pool sized pit full of plastic beads if you want, while your parent scrolls Instagram on a memory foam lily-pad out of sight. Real autonomy—the ability to navigate a city, contribute to a family, or make self-directed choices—requires access to the real world.

In much of the US, public space is chaotic, fragmented, and built for those who can pay their way into curated experiences. We know these places are no safer than public ones (not by a long shot). But the sense of control and exclusion provides useful cover. Instead of building safe and inclusive public spaces in the real world, we get to feel like we’ve opted into something magical and special instead

Disney World is the apotheosis of this curated wonderland concept—an unreal, uncanny space where parents and kids’ relationship with reality, and one another, are transformed. The happiest place on earth.

We are often told (or I was, by my industry-loving parents) that Walt Disney’s great innovation was inventing the idea of family entertainment. He imagined a universe kids and adults could enjoy together and built it whole-cloth from swampland. It’s true. As an adult, I’m thinking about taking my child to Disney World someday. He loves Mickey Mouse. I love Baudrillard, weird applications of social theory, and writing essays. It might be fun for the whole family indeed!

But visiting a fantastical wonderland for kids and adults to enjoy together is not quite the same as enjoying the real world together, and not quite as gratifying. We can give them their wildest fantasies—a river of chocolate, a bouncy castle the size of a real castle. But unless you’re Charlie Bucket, (who at the end of the story, inherits the chocolate factory, having passed Willy Wonka’s twisted test to find a humble and deserving heir) the experience will remain just that: a temporary fantasy.

My real, wildest fantasy come to life would be for the real world to accept that kids are people, too, and should be included in the built environment in public spaces. Imagine a world where parents wouldn’t have to divorce ourselves from reality in order to enjoy our time with kids. I wish the city would invest in indoor public spaces (like it has done with public parks) that were truly inclusive of kids and parents, especially the ones who can’t afford $300/month. Now THAT would be my version of winning a golden ticket.

Enjoyed this Immensely. Off to find that book. Totally agree. Im always shocked when we go to Spain or Portugal (insert any number of countries) and find our kids are welcomed in restaurants and bars like they are actual human beings. In some places in the UK dogs are more welcome than my kids and it drives me mad

My kid brings her own little cart to the local grocery store because they don’t happen to provide them for kids. The looks we get! she handles herself really well there, and some people look down right irritated that she’s shopping. Even in these child-centric places you have authoritative parents and silly rules blocking kids from being themselves fully… Childism makes me sick and it is everywhere.